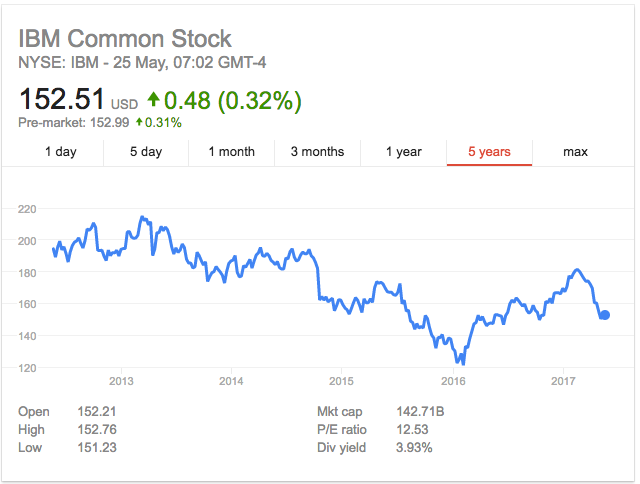

IBM stock was hit severely?in recent month, mostly due to the disappointment from the latest earnings report. It wasn’t a real disappointment, but IBM had a buildup of expectations from their ongoing turnaround, and the recent earnings announcement has poured cold water on the growing enthusiasm. This post is about IBM’s story but carries a moral which applies to many other companies going through disruption in their industry.

IBM is an enormous business with many product lines, intellectual property reserves, large customers/partners ecosystems, and a big pile of cash reserves. IBM has been disrupted in the recent decade by various megatrends, including cloud, mobile computing, software as a service, and others. IBM started a?turnaround which became visible to the investors’ community at the beginning of 2016, a significant change executed quite efficiently across different product lines. This disruption found many other tech companies unprepared, a classic tech disruption where new entrants need to focus only on next-generation products and established players play catch up. It is an unfair situation where the big players carry the burden of what was?not so long ago,?fresh and innovative. IBM turnaround was about refocusing into cognitive computing, a.k.a AI. Although the turnaround is executed very professionally, the shackles of the past prevent them from pleasing the impatient investors’ community.

Can Every Business Turn Around?

A turnaround, or a pivot as coined in the startup world, means to change the business plan of an existing enterprise towards a new market/audience requiring a different set of skills/products/technologies. Pivoting in the startup world is a private case of a?general business turnaround. In a nutshell, every business at any point in time owns a different set of offerings (products/technologies) and cash reserves. Each offering has customers, prospects, partners, and the costs incurred of the creation and the delivery of the offerings to the market. In an industry that is not disrupted, the equation of success is quite simple; the money you make on sales of your offerings should be higher than the attached costs. In the early phases of new market creation, it makes sense to wait for that equation to get into a play by investing more cash in building the right product and establishing excellent access to the market. Disruption is first spotted when it’s hard to grow at the same or higher rate, and fundamental change to the offerings is needed, such as a full rebuild. This?situation happens when new entrants/startups have an economic advantage in entering the market or creating a new overlapping market. When a market is in its early days of disruption, the large enterprises are mostly watching and hoping for the latest trends to fade away. Once the winds of change are blowing too strong, then new thinking is required.

A Disruption is Happening – Now What

Once the changes in the market ring the alarm bell at the top floors, management can take one or more of the following courses of actions:

- Buy into the trend by acquiring technologies/products/teams/early market footprints. The challenges in this course are an efficient absorption of the acquired assets and an adaptation of the existing operations towards a?new direction based on the newly acquired capabilities.

- Create a new line of products and technologies in-house from scratch, realigning existing operations into a dual mode of operation – maintaining the old vs. building the new. Dual offerings that co-exist until a successful internal transfer of leadership to the new product lines take place.

- Build/Invest in a new external entity set to create a future offering in a detached manner. The ultimate and contradicting goal of the new business is to eventually cannibalize the existing product lines towards leadership in the market ? a controlled competitor.

Each path creates a multitude of opportunities and challenges. Eventually, a gameplan should be devised based on the particular posture of the company and the target market supply chain.

Contemplating About A?Turnaround

From a bird’s eye view, all forms of turnarounds have common patterns. Every turnaround has costs. Direct costs of the investment in new products and technologies and indirect costs created due to the organizational transformation. Expenses incurred on top?of keeping the existing business lines healthy and growing. These additional costs are allocated from the cash reserves or?new capital raised from investors. Either way, it is a limited pool of money which requires a well balanced and aggressive plan with almost no room for mistakes. Any mistake will either hurt the innovation efforts or the margins of the current business lines and for public companies, neither is forgivable. Time is also critical here, and fast execution is vital. If mistakes happen, the path can turn into a slippery slope very quickly.

Besides the financial challenges in running a successful turnaround, there are many psychological, emotional, and organizational issues hanging in the air. First and foremost is the feeling of loss around sunk cost. Usually, before a turnaround is grasped, there are many efforts to revive existing business lines with different investment options such as linear evolution in products, reorganizations, rebranding, and new partnerships. These cost a lot of money, and until the understanding that it is not going to work finally sinks, the burden of sunk costs has grown very fast. The second big issue is the impact of a turnaround on the organizational chart. People tend not to like changes and turnarounds. The top management is hyper-motivated?thanks to the optimistic change consultants, but the employees who make the hierarchies do not necessarily see the full picture nor care about it. It goes down to every single individual who is part of the change, their thoughts about the impact on their career as well as their likings and aspirations. Spreading the move across the organization is a kind of black magic, and the ones who know how to do that are very rare. The key to a successful organizational change is to have change agents coming from within and not letting the change driven by the consultants who are perceived as many times as overnight guests. The third strategic concern is the underlying fear of cannibalization.?Often, the successful path of a turnaround is death to existing business lines, and getting support for that across the board is somewhat problematic.

Should IBM Divest?

A tough question for an outsider like me, and I guess pretty challenging even if you are an insider. My point of view is that IBM has reached a firm stance in AI, which is becoming more challenging to maintain over time. AI has, in magnitude, more potential than the rest of the business, and these unique assets should be freed from the burden of the other lines of business. IBM should maintain the strategic connections to the other divisions as they are probably the best distribution channels for those cognitive capabilities.

The Private Case of Startup Pivots

A pivot in startups is tricky and risky. First, there is the psychological barrier of admitting that the direction is wrong. Contradicting the general atmosphere of boundless startup optimism is a challenge. On top of that, there will always be enough naysayers that will complain that there is not sufficient proof that the startup is indeed in the wrong direction. Needless to talk about the disbelievers that will require seeing evidence before going into the new direction. Quite tricky to rationalize plans when decision making is anyway full of intuitions with minimal history. Due to the limited history of many startups and dependence on cash infusion, a pivot, even if justified, is many times a killer. There aren’t too many people in general who have the mental flexibility for a pivot, and you need everyone in the startup on board. The very few pivots I saw that were successful did well thanks to incredible leadership, which made everyone follow it half blindly – ?a leap of faith.

Food for thought – How come we rarely see disruptors buying established disrupted players to gain a fast market footprint?